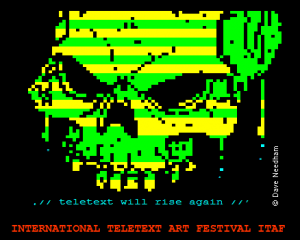

I first heard about International Teletext Art Festival 2012 through the Teletext Mailing List a couple of months back, but the desire to have works published via public teletext first arose some five years ago, during the research stages of my Pixel is Power dissertation.

I considered contacting British teletext broadcasters to discuss the possibility of them carrying my work, but like so many pipe dreams, that idea was slowly pushed to the back of the cupboard as the project progressed and priorities changed. The recent ITAF open call for submissions offered the perfect opportunity to finish what I never really started and finally get some artwork shown on actual teletext and not some second rate backwater internet squat – Pixel is Power would get some long-deserved closure. Well, of sorts, since it’s kind of a never-ending ongoing thing. Yeah, expect to see Harry Yack exhibiting at ITAF2040.

It had been so long since I last opened my teletext editor that I half expected the gears in my computation device to seize up when I double clicked the Cebratext icon, which had been relegated to the ‘Unused Desktop Shortcuts’ folder like a FIFA update that’s out of date before it’s even released. But to my surprise, it worked almost perfectly and I was cutting and pasting those low-res building blocks like it was 2007 once again. Before I knew it I was creating stuff far superior to those experiments I threw together after first downloading the program, and the Pixel is Power was not only back on the road, but thundering along like an HGV stacked to the brim with industrial lard careering down a 50% decline.

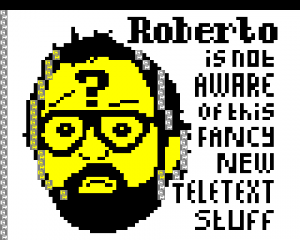

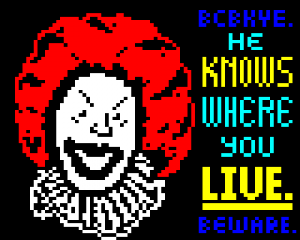

Just to tease any lingering bugs out of the Harry Yack-Cebratext machine, I started by chopping up a few recent vector bits and bobs before converting them to the teletext format. Naturally, a lot of these pertained to Illogicopedia, so where better place to start than ‘mascots’ Roberto and Bcbkye?

Around this time, you begin to get to grips with the limitations, or should I say idiosyncrasies of the format. Teletext, or at least Cebratext, allows you to paint one colour on a black (blank) background, and for each instance you would like to use a different colour you must insert a 3*2 pixel data marker (shown in the image to the above right) in an exclusively black area. Note that Roberto’s beard/hair never covers an area less than 2 pixels in width: this is where the yellow and white colour markers are placed.

Rendering text is a little more hit-and-miss than images. You can generate and tinker with the letters in an image editing program, but it will only get you so far because the vast majority of fonts don’t translate very well to such a small working area. The stylised ‘banana’ font required a certain amount of post-import tinkering to negate ‘pixel merging’ for it to be legible. Text in the Bcbkye image, on the other hand, was ‘hand painted’ using Cebratext itself, which, while more time consuming, is satisfying for the sole reason it just feels like teletext. The format was never about fancy fonts and cutting edge graphics (though you can’t deny teletext was, for a long period, state-of-the-art), but clear interfaces and the convenience of simplicity.

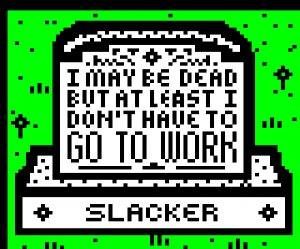

Teletext is, through time period association, often linked with a specific sense of humour. That ‘grin and bear it’, frequently dark and realistic approach to comedy is tempered by the bright, cartoon strip colour palette to create something essentially very British, yet at the same time very teletext. It’s hard to quantify, but look no further than the 1980s homebrew video game scene and you’ll get a rough idea of what I’m trying to communicate. This sense of humour is something I attempted to encapsulate in At Least I Don’t Have to go to Work, very probably my favourite entry. ITAF chose this piece to represent my submissions on their homepage for the event, and I can understand why – it has just the right cheese factor that, to me, typifies teletext.

Followers of my Twitter account will recognise the creature in I’ll be Yak as my avatar. The ‘Yak Terminator’ was originally drawn for me by the massively talented Huge Bob of Guffaw Comics, and will, in my eyes anyway, serve as my own identifier at this event. I can certainly see it making an appearance as my YouTube thumbnail at some point in the future. Thanks once again, Bob!

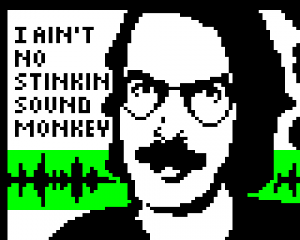

The bloke playing Pong is actually doing so on a teletext programming machine. I don’t know if that is or ever has been physically possible, but for the purposes of the piece, let’s say he’s taking a break from his news-coding duties with a bit of joystick waggling action. A quick glance at the source image reveals he was in fact busy programming a travel news page, so let it be known that this gentleman certainly was not slacking, and this piece was just me being a bit cheeky. Plus I wanted to get a reference to video games, no matter how small, into at least one of my submissions.

Ah, Zenith Space Command: the grandaddy of the modern remote control, a pioneer of televisual convenience. It’s fairly safe to assume that without a zapper, teletext wouldn’t have been quite as successful. Teletext, and indeed much of modern television as we know it is indebted to the Space Command, which allowed users to change the channel from the comfort of their own sofas; gone were the days of poking at buttons with a broom handle. I think it’s done more than enough to earn its place in the Teletext Hall of Fame, don’t you?

Continuing the video game theme, here’s one I didn’t submit: my own tribute to fungus-fancier Mario Mario, better known to his friends and millions upon millions of joypad-pummelers (yup, the late-80s successor to joystick-wagglers) as Super Mario. Why no submit? Well, it’s already been done by Paul Davis. Consider this my homage to him, if you will.

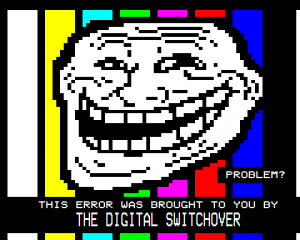

So what does the future hold for our good friend? Sadly, it doesn’t look good – the digital switchover is ravaging teletext systems across the globe and many nations have already bid their final goodbyes to the format. Britain is in the final stages of its own teletext switch-off, and there are but months remaining of the traditional analogue signal. It feels weird having to attach a little box to your telly in order to receive terrestrial channels, but that’s just the way it is because Stone Cold (AKA the BBC) said so. My parting jab serves as a gentle ‘screw you’ to the ones signing teletext’s death warrant, casting them as the proverbial internet trolls in this tragedy of Ancient Greek proportions.

There is, however, a glimmer of hope, for the very medium which has accelerated the demise of teletext may provide an opportunity for its spirit to live on. Indeed, I would never have known of this festival if it weren’t for the web and Fixc, the artists co-operative responsible for its staging. I think we’re still quite a long way from Windows Teletext 2.0 at this moment in time, but thanks to ITAF12, we’re one step closer.

- View all entries for International Teletext Art Festival 2012 here until 8 April, or my own stuff here.

- See more info on the participating artists here.

2 thoughts to “My submissions for International Teletext Art Festival 2012: Walkthrough”